This post also has a Podcast Version.

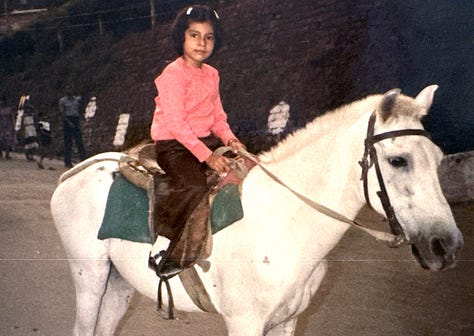

I had a very privileged childhood. Growing up in India as an only child at a time when female infanticides were prevalent and when families almost never “gave up” until they had a boy, you’d probably assume I was loved dearly and treated like a princess.

I was. But I also had a very unhappy childhood fraught with admonishments, loud, harsh arguments between my parents, and a deep sense of feeling unwanted.

They worked hard to make sure I was well taken care of. Their middle class life was not going to be my inheritance. I’d get a “proper” education, a decent shot at a good career and all the books my curious heart desired. After all, I had the brains to be a lawyer, a doctor or an engineer — the trifecta of professions that were deemed worthy and respectable. They were going to make sure of that.

I was always made painfully aware that I had to live up to their expectations, both overt and implicit. The implicit ones were the most deafening. The sighs, the head shakes, the drooping shoulders.

Despite consistently making it to the top 3 or top 5 in my elementary school, with a section size of 44 in any given grade, I never heard the word “congratulations.” There was no pride in my parent’s eyes … just that look of disappointment. And the silence. Followed by “who came first?” My two A’s that I worked so hard to get, didn’t matter when there were so many B pluses.

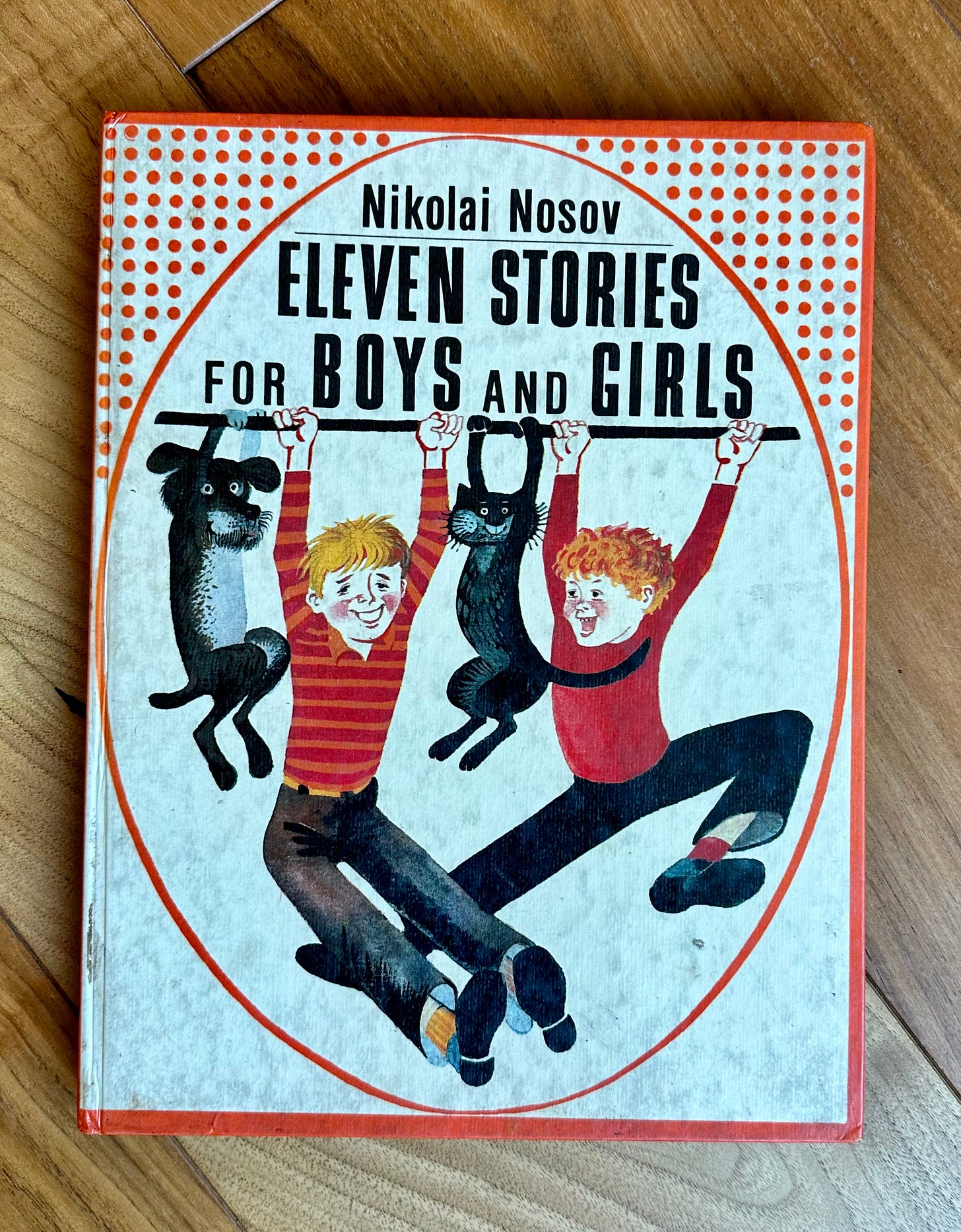

The only time I ever came first was in 4th grade — Miss Greene’s class. I still have the book I was awarded. And I distinctly remember my dad’s reaction: “This is great! Now why can’t you do this every year?”

Even now — all these years later — it makes me tear up.

…..

There were many things I enjoyed participating in: choir, art, relay races … all the competitions where I could have a chance to win gold, to be on the top, to show them that I bested everyone! But what I looked forward to most each year were the elocution contests. I loved working with my English teacher on voice modulation and stage presence.

As I walked up the stage, I’d always feel a tightness in my chest and my mind would be completely blank. Stepping up to the mic, my eyes would frantically scan the audience until they rested on my dad. He never failed to attend these. And then the words came. Followed by the standing applause and the adulations. I was really good at it … but I didn’t have a perfect record.

The only time I came second in 13 years of competing, was when I recited Casabianca. I can still see my dad’s face … the corners of his mouth turned upward, his hands clapping in slow motion and his deep-set eyes vacant and emotionless.

Nothing I did was good enough … when I was made vice-captain of my house based on teacher recommendations gathered over 12 years, my dad’s response was “who got selected as school captain?” And my mom asked, “And why wasn’t it you?”

The silent tears. I remember wetting my pillow almost every night.

…..

While my dad was an “engaged” parent, my mom was completely checked out. She had a career to focus on, a glass ceiling to break, a bigger paycheck and more awards to garner. She wasn’t “just a clerk” at a bank … she was the bank manager, a formidable role for a woman in her 40’s to be at that time. It was a traditional, male-dominated field, and my mom felt that her worth as a woman was intrinsically tied to her ability to bring home the bacon. In my mother's eyes, financial independence was the ultimate form of empowerment, the only way to truly have a voice and be taken seriously in a society that often dismissed and undervalued women.

She basked in that feeling of “being important” and I know how desperately she wanted the same for me … a position of authority, financial independence, and respect that comes from that kind of stature.

But does it? Did people defer to her because of her leadership style or were they afraid of her because of her title? There was a nuanced difference in my mind … but my thoughts didn’t matter. I was just supposed to do what I was told … I was the child. They were the parents. It was as simple as that.

There was no concept of mutual respect, a desire to know what I wanted, or even any time set aside to ask me how my day went, how I was feeling, who I was hanging out with. Their focus was only on the report card.

My entire academic career was a string of failures in their eyes.

And I know — if they were to ever read this — they would invalidate all my “sensitive” feelings with the phrase “we were only trying to push you harder because we knew you could do better.”

Despite their daily arguments, which almost always centered around money, they were united on that front.

And I am not oblivious to their point of view. They wanted me to be a responsible, hardworking, resilient, ambitious individual who could earn her own keep. I get that. They were simply looking out for me, in a way that parents of that generation and our culture knew how to.

That said, I was the one who had to carry the burden of their dreams.

When I fainted in high school while dissecting a rat — the only 15-year-old ever in the history of that school to have dropped cold to the floor at the sight of a twitching aorta — they knew medical school was out of the question. And with math never being my strong suit, engineering was promptly crossed off the list as well.

Desperate for direction, my parents consulted their lawyer friends, seeking a path that would lead to a prosperous future. But instead of legal briefs and courtrooms, they were met with a different kind of advice: business school. That, they were assured, was where the real money was to be made.

So I did as I was told — the only concession my parents made was let me choose Psychology as my second major after Economics and English as a minor. Why? My high school biology teacher — the same one who had witnessed my dramatic fainting episode — had became my most fervent advocate.

She had seen another side of me: the poet, the wordsmith. Unbeknownst to my parents, I had been quietly winning poetry competitions and publishing my work in teen magazines.

She saw potential in my writing, a spark of creativity that could ignite a successful career. But she also pre-empted their apprehension about a writing “career,” or lack thereof with the all-too-common perception that writers languish in poverty, their talents undervalued and their wallets empty. She was astute and recognized that my passion for language and storytelling could translate into a fulfilling career in psychology, where communication and empathy are paramount.

So, she planted a seed in my parents' minds: Psychology. It was a strategic backup plan, a safety net in case the business world proved too cutthroat. Close enough to being a “doctor,” my parents concurred. And that was settled.

I did not disappoint! I got the highest marks in psychology in the state — the state!

But my elation was short-lived, overshadowed by the looming specter of my. performance in economics. Despite countless hours spent poring over textbooks and attending extra tutoring sessions, I had barely scraped by, just managing to pass the required coursework. I really didn’t care for anything that had anything to do with money. Yet, my parents were determined. So, I sat for every single MBA entrance exam there was at that time in the country.

Each rejection letter from business schools felt like a personal failure, a betrayal of their aspirations.

Their arguments became a relentless storm, thunderous clashes that shook the very foundation of our home. The walls seemed to close in, suffocating me. It was during this time that I found solace in watercolor painting. When words failed me, when the pain became too unbearable to express, I turned to my brushes. Each stroke was a silent scream, a cathartic release of emotions too raw for language.

…….

As they shared their disappointments within their own social circle, someone suggested that they let me sit for the entrance exam at one of the premier design institutes in India … “you’ve already tried to push her in one direction, perhaps let her have a shot at something she’s actually good at?” said a sage man who had their ear. And since the National Institute of Design was recognized by the Government of India as a “Scientific and Industrial Research Organization,” they decided it was prestigious enough.

I went through the rigors of a three-month training program in Delhi, just so I could ace the the intense three-day entrance exam. It was a huge deal for my parents to allow this. There was no scope for failure. I simply had to get in!

And I made it to the final interview where I was met by an elite group of accomplished artists, movie directors and fine art connoisseurs. Their consensus after flipping through a portfolio that felt like an extension of myself? “Thank you for coming but we find your work unimaginative and unoriginal … you have average talent.” They suggested a career in writing. Maybe?

Tears. Shame. The one chance I had to show my parents that I could be good at something.

Perhaps, they were correct. I wouldn’t amount to anything. And so, they resigned themselves to the inevitable, to the path that countless other parents before them had trod: they would find me a "suitable match," a husband who could provide the financial security and social standing that they had envisioned for me.

…..

But I guess, the interview setback in some way solidified my backup plan. Broken-hearted I decided to pack away my paints, but continued to write. Small freelance op-eds for the local daily; a couple of reports for another national magazine; a short stint at our local radio station ...Sneakily, I had applied for a writing position with a publishing house in Bombay. Within three days of my application, the hiring manager called. A 45-minute phone interview ensued. I was trembling, but steadied my voice. This job, this glimmer of hope, could be my salvation, a validation of my “skills.” If I could prove my writing was worthy of a paycheck, maybe, just maybe, I could sway my parents.

For 48 agonizing hours, I became a prisoner of anticipation. I haunted our dial-up modem, its tortuous chugging tormenting me as I obsessively refreshed my inbox. I hovered by the phone, my heart skipping a beat with every ring. Perhaps, they would call instead of email?

And then it came. The offer letter. They wanted me to start in a week. They believed in me.

They believed in me.

I had one week to convince my parents that I could make something of myself.

Surprise. A tinge of disappointment. Anxiety. Those were the three emotions my parents exhibited when I broke the news. My mom gave me six months to prove myself. It was a fragile victory, a tentative truce in the ongoing battle for my future, but it was a victory nonetheless.

….

My life took a turn once I reached Bombay … and you’ll learn more about it in future podcasts. I found my biggest advocate, my staunchest supporter, my loudest cheerleader whom I owe this version of myself. My husband. But as I said, more on that later.

….

For as long as I can remember, I’ve carried this burden of trying to do better than my best, overcommitting and spreading myself thin, feeling physically and mentally exhausted and emotionally drained. And ultimately living with that gnawing feeling that I have failed to live up to the lofty ideals of those who brought me into this world.

Need it have been so cruel? So painful? So lonely?

It has been a repetitive cycle of self-doubt, hustling, trying to prove myself and never really tasting (the authentic flavor of) success, whatever that means.

As a parent myself, I recognize – perhaps more acutely than my husband – the profound impact my words and actions have on our daughter. I see how my subtle slights and casual indifferences can sting, how my authentic praise and warm hugs can uplift, how my raised voice or arched eyebrow can trigger a cascade of emotions within her.

I am deeply and constantly aware of the power I wield over her simply by virtue of being her mother — a power that comes with an immense responsibility to nurture her self-esteem, to cultivate her confidence, and to earn her trust and respect every single day.

It's a delicate dance, this parenting thing. A constant balancing act of offering encouragement without resorting to empty platitudes or imposing unrealistic expectations. It's about gently nudging her towards growth and improvement, all while nurturing a resilient sense of self-belief. It's about helping her discover the profound joy and fulfillment that comes from immersing herself in the process and enjoying it vis-a-vis the bullishness of achieving that perfect outcome.

I’m not perfect. I’m not better. I mess up. But I also own up to being imperfect. And, perhaps, I am more attuned to her feelings than my parents were to mine. Perhaps, I can understand better when her idea of “happiness” doesn’t align with mine. Perhaps, I can relate more to her internal dialogue because of the conversations I continue to have with myself.

Parenting her is a journey of continuous learning and adaptation. As she changes, I evolve, too. I make it my priority to be present for her while simultaneously exercising restraint, allowing her the space to discover her own path, her own self. She's opened my eyes to new perspectives, challenged my assumptions, and taught me invaluable lessons about life and love. In many ways, I feel like she's the one shaping me, guiding me towards a better version of myself.

….

I owe my life to my parents. They filled my childhood with material comforts, ensuring I never lacked for anything. In many ways, I had a privileged upbringing, one filled with opportunities and experiences. They did their best and I can never fault them for that.

But as an adult approaching the mid-point of my own life journey, a lingering ache remains. A longing for the unconditional love and acceptance that every child craves. I can't help but wonder if, amidst their well-intentioned efforts, they could have paused, truly seen me, and embraced the child I was, instead of making me feel like they wanted someone else. Someone better.

It's been a lifelong, soul-crushing battle to please them. From the six-year-old desperately seeking acknowledgment (not even appreciation) of her crayon drawings to the 35-year-old giving up her flourishing career to be a stay-at-home-mom, I’ve never gotten it right.

The most painful part is that when I finally mustered the courage last year to express the deep-seated hurt I've carried for so long, their response was dismissive. "Oh, stop making things up!" they retorted, "We've always told everyone how proud we are of you!"

People.

Not me.

Never me.

The one person who needed to hear it the most.

Their words only deepened the wound, revealing this gulf between their perception of me and the reality of my lived experience.

It's ironical to be praised publicly while feeling so profoundly unseen at home.

…..

I cannot simply shrug off the weight of years of feeling "less than" with a few trite words of optimism.

I’d be dishonest if I said that a part of me still isn’t waiting for their approval, their recognition of my worth. It's a struggle to reconcile the daughter they raised with the woman I've become, a woman who has achieved success on her own terms, yet still grapples with the echoes of their unmet expectations.

As I slowly let go of these deep-rooted insecurities, I find solace and hope in the relationship we are nurturing with our own daughter. It's a bond built on open communication, unconditional love, and mutual respect — the very foundation I yearned for as a child.

She has had a privileged childhood, too, but I hope it’s one that makes her feel empowered to embrace her true self with unwavering confidence and self-love.

Very well written. I'm almost 71 years old and also an only child. I grew up in the US, and was not pushed to a specific profession, but always had the sense that I needed to be the best. My parents were loving but not very hugging and rarely congratulatory. I almost wonder if that is a generational thing. However, my dear Dad, after my Mom had passed away, once introduced me as his best friend. There was no higher praise. I think I made them proud. I did better than the children of their friends and family. So I'm going to take that best friend comment as a success!!

I hear you, Mansi! And I felt you ... your night vs. day descriptions of your parents' reactions to who they wanted you to be vs. who you really are ... your silent hope for their approval and encouragement to which they were oblivious ... the pearls of talent, wisdom and joy within you to which they were completely blind.

My childhood was half & half. My mom totally "got" me and saw all my dimensions and potential; my dad only recognized the few pieces of me that were like him. Somehow, I survived my childhood with my self-esteem mostly intact.

You write beautifully. You are brave. Your daughter is so fortunate to have you! I am humbled by your honesty, your commitment to opening up to us "strangers" and the strength you have to invite our reactions. I hope you feel the virtual hug I am sending you ...